We’re nearing the end of Week Two over at Ball State University’s Gender Through Comics, (Twitter hashtag: #SuperMOOC), and we’ve been reading Superman Birthright by veteran comics writer, Mark Waid. I enjoyed listening to Instructor Christy Blanch’s interview with Mark last Thursday, which actually led me to pick up Birthright again–I’d put it down after 1 1/2 issues on Wednesday night, cause I just couldn’t get into it. But it definitely started to come together for me, and I’m glad that I’m now much more acquainted with one of the world’s oldest superheroes.

I’ve developed my own thesis by which to tackle Superman: he reflects our evolving notion of masculine idealism. A lot has changed in terms of how we perceive the “perfect” man or woman in the last 100 years. Superman keeps getting re-invented to reflect this. But what connects them? How is the Superman of the 1930s’ Action Comics still Superman just as much as Clark Kent in Superman Birthright? Maybe, to do this, we should look at what is noticeably different?

Kent’s Vegetarianism

This is an interesting update–one that Mark Waid touched on in the interview, explaining that this wasn’t intended to just be New Age mumbo-jumbo, and I agree. I think he is effectively exploring a higher understanding by way of Kent’s alien super-abilities. I believe this to be one of the many positive effects of sci-fi culture on modern pop culture, equivalent to Christianity’s influences of divine idealism on the Renaissance, if that makes any sense. That is, we as humans develop notions that don’t actually exist, but come into existence by us imagining them as notions of God or another higher being, like an alien. Thus we develop interpretations of inalienable rights, Utopias, …. and, well, places where we don’t have to kill other living things just to survive. That is an idealism entrenched in lots of Sci-Fi, and Waid has selected it as a “Superman” trait. I think this was an excellent decision, and emphasizes that an ideal masculine trait, now, is to be able to empathize and connect with life around you.

Kent begins his identity as Superman by travelling the world and searching out knowledge and adventure. This is compared to Pa Kent’s time in the Army in Issue #3 of Birthright, but it reminds me a lot of Che Guevera in the chapter of his life when he wrote his Motorcycle Diaries. It reflects a deliberate and positive step in the maturation process.

This ‘search for himself’ is coupled with the reality that Kent struggles with his identity and the gap that exists between himself and his [not-so-fellow] man. He describes that it never takes long for his relationships with other people being to break down, once his abilities become known. “Invariably, they freak,” he says. “They become retroactively paranoid, wondering what else Clark Kent is hiding from them.”

This ‘search for himself’ is coupled with the reality that Kent struggles with his identity and the gap that exists between himself and his [not-so-fellow] man. He describes that it never takes long for his relationships with other people being to break down, once his abilities become known. “Invariably, they freak,” he says. “They become retroactively paranoid, wondering what else Clark Kent is hiding from them.”

In my mind, this narrative runs parallel to the concept of privilege. In addition to being an alien with superhuman abilities, Clark Kent also happens to be an able-bodied white male, who was raised in the most powerful and militarily aggressive country on Earth: the United States. It shows him attempting to make friends with non-Americans in his travels, to no avail once they discover just how much more powerful [privileged?] he is than they are.

He struggles with balancing his desire to help people without isolating himself from them. He longs to be accepted as a human.

When Kent tries to advise a local African leader not to march because he foresees violence against him, the villagers are right to point out that he is a white outsider trying to dictate to them. It doesn’t mean Kent has bad intentions, and some readers may think that this objection makes the characters simple and petty, but there is real history and politics there that he is not, or has chosen not to be, aware of. If anything Waid downplays this in the story; in real life, I think a man like Kent would be facing serious trust issues well before he started lifting buildings.

When Kent tries to advise a local African leader not to march because he foresees violence against him, the villagers are right to point out that he is a white outsider trying to dictate to them. It doesn’t mean Kent has bad intentions, and some readers may think that this objection makes the characters simple and petty, but there is real history and politics there that he is not, or has chosen not to be, aware of. If anything Waid downplays this in the story; in real life, I think a man like Kent would be facing serious trust issues well before he started lifting buildings.

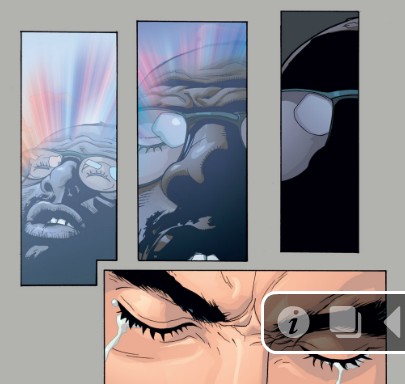

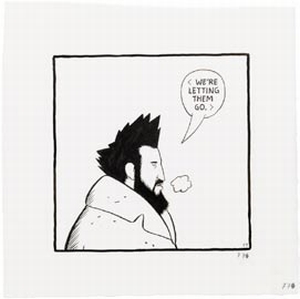

On this note, I can’t help but point out that a summary of this plot line smells a bit of “white man’s burden”. Kent wants to help people who need help the most, so he goes to help a minority tribe in Africa. Some of the images depicting this are particularly noteworthy, like this one to the right, which could also be critiqued from a perspective of gender as well as race. What can I say? It’s hard to write realistic stories without touching real-life issues like politics, gender dynamics, race relations, histories of colonialism and imperialism, etc. Comics have traditionally been comfortable in their own universe[s], but that is slowly, slowly changing, and I think panels like this are an indication of both an attempt to be more real, while also clinging to old stereotypes. (I mean, really, how long has Abena known Kent? Two weeks? If I were her and this guy came out of no-where with mega perception and rock-hard abs, I’d think he was CIA–hands down.)

Waid uses a great term in the #SuperMOOC interview: comics are a “visual short-hand” form of storytelling. I acknowledge that it’s hard not to simplify human conditions and relationships. Duly noted, but I wouldn’t be doin’ my job if I didn’t point this stuff out.

A side-note: The epitomy of “cheeziness” is the absence of believability. Superhero stories are in a constant struggle to maintain believability. To do that, Superman is all about depicting things on the edge of what we can sense and understand: that means everything from the constant introduction of new concepts (logically), to the depiction of senses that we find difficult or impossible to detect, such as superhuman sight, hearing, and movement. The illustrations in Birthright are vital to this, and really carry the story.

Superman crying: this is part of the evolution of masculine idealism, as well as the creative struggle for believability. The idea that men are supposed to hide their emotions is thankfully falling out of date as a prejudice that is both detrimental to men and world around them. Furthermore, emotion is an essential element within the anatomy of epic narrative: battles where life and death hang in a balance must make emotional connections. Crying , at least for any writer worth their salt, is not a sign of weakness in a character, but an indicator that they understand and are intimately connected with that world. As well, we ideally expect to see story characters crying around the points in the story when we, the readers, feel like crying. This connects the protagonist not only to the world around them, but to their audience as well, and creates a better story experience.

Part of Superman’s modern-day struggle, invariably, becomes one of masculine idealism vs. realism: can a near-perfect man exist in an imperfect world? Since man can influence the world through his abilities and actions, and this man does, despite the world remaining imperfect—is he still a perfect man / an ideal? Is he still “Superman”?

Part of Superman’s modern-day struggle, invariably, becomes one of masculine idealism vs. realism: can a near-perfect man exist in an imperfect world? Since man can influence the world through his abilities and actions, and this man does, despite the world remaining imperfect—is he still a perfect man / an ideal? Is he still “Superman”?

Superman has traditionally had a strong father-son bond. This is a part of masculine idealism: ideal men come from ideal father-son relationships. This explains the place of prominence for Kah-el (Clark Kent’s birth father) in previous Superman narratives—as well as Pa Kent.

Pa Kent and Clark struggle to understand their connection, now that Clark wants to explore his extraterrestrial roots.

Superman is always an optimist. This distinguishes him from new superheroes, who are often expected to take on a “more realistic” perspective on the world, as well as old superheroes who have been reinvented within the modern “anti-hero” framework.

What to make of Lois Lane?

Superman is as much a reflection of the evolution of gender perceptions as just about any pop culture icon that outlasts a generation. But what do we make of Lois Lane? In the very first Superman comics, Lane was a very attractive, feisty and smart news reporter who is dedicated to her career and her independence, despite the occasional dramatic lapse of utter dependence on Superman and his supernatural abilities. In the most recent remakes of Superman, we see Lane as…. A very attractive, feisty and smart news reporter who is dedicated to her career and her independence, despite ALSO having the occasional dramatic lapse of utter dependence on Superman and his supernatural abilities. Despite some subtle changes, (and one really confusing case of Lois Lane turning Black for a day), the woman has remained much more glued to her original form.

Superman is as much a reflection of the evolution of gender perceptions as just about any pop culture icon that outlasts a generation. But what do we make of Lois Lane? In the very first Superman comics, Lane was a very attractive, feisty and smart news reporter who is dedicated to her career and her independence, despite the occasional dramatic lapse of utter dependence on Superman and his supernatural abilities. In the most recent remakes of Superman, we see Lane as…. A very attractive, feisty and smart news reporter who is dedicated to her career and her independence, despite ALSO having the occasional dramatic lapse of utter dependence on Superman and his supernatural abilities. Despite some subtle changes, (and one really confusing case of Lois Lane turning Black for a day), the woman has remained much more glued to her original form.

If Superman has changed so much over 75 years, why not Lane? Was Lois Lane classic, at in her inception, already a progressive enough reflection of the female gender? Are comic creators’ notions of women and their ‘social evolution’ simply stagnant—it just doesn’t get any better? I’m unsure about this one, and want to give it some future thought. I actually think that it presents an interesting argument: gender perceptions of men have changed more than women in the history of comics. This is despite massive social, political, and economic changes in the status of women in that time.

I’m looking forward to reading others’ thoughts on this, as we continue with the #SuperMOOC class. Thanks for reading. More to come with Week 3.

Our first set of reading material for the week is a collection of work by comics creator Terry Moore: Strangers in Paradise, Vols I and II; and Rachel Rising.

Our first set of reading material for the week is a collection of work by comics creator Terry Moore: Strangers in Paradise, Vols I and II; and Rachel Rising.

N: Conversely, why did comics seem like the art medium to go with for a political art project?

N: Conversely, why did comics seem like the art medium to go with for a political art project?

BAYOU – 2010, by Jeremy Love.

BAYOU – 2010, by Jeremy Love. NAT TURNER – 2006 by Kyle Baker. Four issues bound into two volumes here tell the story of Nathaniel “Nat” Turner, leader of one of the largest slave revolts in American history. The genius of this comic is that it tells a compelling story while allowing the historical value to shine through. It uses all excepts of Nat Turner’s own words, taken from a “confession” he gave to a newspaper while in prison awaiting his execution (the word “confession” of course, is an editorialization from the newspaper of the time–however, one can hardly expect him to be remorseful for killing the men who killed and enslaved his kinfolk). We not only have a primary source, but a first-hand account of what we’re seeing depicted in pictures: the life of a 19th Century slave, the horror of life from capture, transport, sale, work, and punishment. The role of religion and prayer for slaves who survived. As a political and historical comics enthusiast, this is one of the gems. Kyle Baker looks to have taken 19th Century newspaper illustrations and breathed them full of life and human emotion. This and a nail-biting narration have practically gift-wrapped this bloody episode of American history.

NAT TURNER – 2006 by Kyle Baker. Four issues bound into two volumes here tell the story of Nathaniel “Nat” Turner, leader of one of the largest slave revolts in American history. The genius of this comic is that it tells a compelling story while allowing the historical value to shine through. It uses all excepts of Nat Turner’s own words, taken from a “confession” he gave to a newspaper while in prison awaiting his execution (the word “confession” of course, is an editorialization from the newspaper of the time–however, one can hardly expect him to be remorseful for killing the men who killed and enslaved his kinfolk). We not only have a primary source, but a first-hand account of what we’re seeing depicted in pictures: the life of a 19th Century slave, the horror of life from capture, transport, sale, work, and punishment. The role of religion and prayer for slaves who survived. As a political and historical comics enthusiast, this is one of the gems. Kyle Baker looks to have taken 19th Century newspaper illustrations and breathed them full of life and human emotion. This and a nail-biting narration have practically gift-wrapped this bloody episode of American history. JACKIE ROBINSON, Issues 0 – 6 – Written by sports-writer Charles Dexter. Now I know nothing about this comic – save that it was published in 1950 and that it’s real. That makes it one of the earliest comic book depictions of a black historical figure (maybe the first?) and impossible to leave off this list, where I try to encourage that there is black representation, but also a note-worthy link to Black History (sorry Black Panther, Storm, Huey Freeman…)

JACKIE ROBINSON, Issues 0 – 6 – Written by sports-writer Charles Dexter. Now I know nothing about this comic – save that it was published in 1950 and that it’s real. That makes it one of the earliest comic book depictions of a black historical figure (maybe the first?) and impossible to leave off this list, where I try to encourage that there is black representation, but also a note-worthy link to Black History (sorry Black Panther, Storm, Huey Freeman…)

KING: A COMICS BIOGRAPHY OF MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. – 2005, by Ho Che Anderson. Generally considered to be more comics journalism, this volume collects over 10 years of Ho Che Anderson’s work into a biography of the renowned civil rights leader. From a review on Amazing: “KING probes the life story of one of America’s greatest public figures with an unflinchingly critical eye, casting King as an ambitious, dichotomous figure deserving of his place in history but not above moral sacrifice to get there. Anderson’s expressionistic visual style is wrought with dramatic energy; panels evoke a painterly attention to detail but juxtapose with one another in such a way as to propel King’s story with cinematic momentum.”

KING: A COMICS BIOGRAPHY OF MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. – 2005, by Ho Che Anderson. Generally considered to be more comics journalism, this volume collects over 10 years of Ho Che Anderson’s work into a biography of the renowned civil rights leader. From a review on Amazing: “KING probes the life story of one of America’s greatest public figures with an unflinchingly critical eye, casting King as an ambitious, dichotomous figure deserving of his place in history but not above moral sacrifice to get there. Anderson’s expressionistic visual style is wrought with dramatic energy; panels evoke a painterly attention to detail but juxtapose with one another in such a way as to propel King’s story with cinematic momentum.” BIRTH OF A NATION – 2004, by Aaron McGruder and Reginald Hudlin and Kyle Baker.

BIRTH OF A NATION – 2004, by Aaron McGruder and Reginald Hudlin and Kyle Baker. “STILL I RISE”: A GRAPHIC HISTORY OF AFRICAN AMERICANS – 2009, by Roland Laird (Author), Taneshia Nash Laird (Author), Elihu “Adofo” Bey (Illustrator), Charles Johnson (Foreword)

“STILL I RISE”: A GRAPHIC HISTORY OF AFRICAN AMERICANS – 2009, by Roland Laird (Author), Taneshia Nash Laird (Author), Elihu “Adofo” Bey (Illustrator), Charles Johnson (Foreword)