Title: CHE: a graphic biography

Title: CHE: a graphic biography

Author and Artist: Spain Rodriguez

Published: 2008 (Verso Books)

Editor: Paul Buhle (also contributed an afterword on Che, co-written with Sarah Seidman)

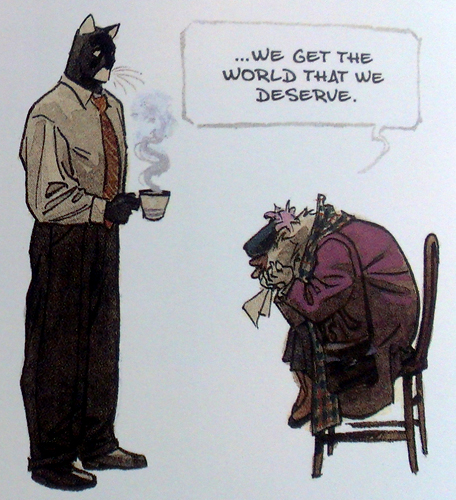

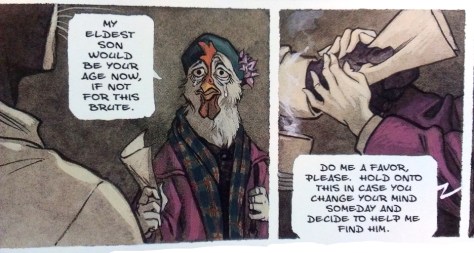

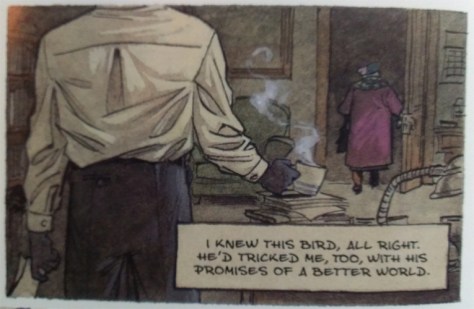

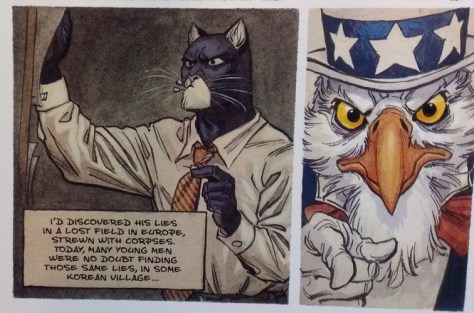

As something of a legend in his own right, comics maker Spain Rodriguez had this Graphic Biography of Che Guevera out before the three others I have reviewed here. I wish he were still alive today, because I’d love to ask him what compelled him personally to do this piece—and furthermore, why a bunch of other people got interested in similar projects right around the same time.

Of all of the books, his has a decidedly indie style (that’s Spain for you). It was also the only work that was by a single person, not a team of writer-and-illustrator. What his visuals lack for in polish, they make up for in detail. On page 39 it shows Che getting grazed in the neck during the early days of the July 26 Movement. Nothing more is said of his wound, but there’s still a bandage on his neck by page 40, several panels later. Call me a freak but I appreciate that.

The content of the text is also excellent. Spain’s points of interest are focused, relevant, and well-argued where arguable. He goes beyond just rhetoric in quoting Che, choosing instead soundbites that let you hear the gears turning in this remarkable man’s head. This is the first book to touch on the factional disputes and internal dynamics of the July 26th Movement and the Cuban Revolution as a whole, which means that Spain believed what I believe: you can’t understand Ernesto Guevara without understanding the Cuban Revolution. If this seems too ideological, too political, well,… Try reading a biography of Thomas Jefferson without coming across the line, “We the People…” .

His narrative of the Bay of Pigs / Playa Giron is amazing—a really great piece of comic art. Great flow; not too text-heavy; educational; beautiful. There’s even a rare moment that Rodriguez is able to place himself in the story, to explain where he was and how he was feeling during the Cuban Missile Crisis. It was his generation’s take on my “Where were you on September 11th?” and I find it intriguing.

In my opinion, Spain’s Graphic Biography is the victor of this 3 week Battle of the Graphic Biographies. In all fairness, he had quite a head-start on the others. Aside from literally being the first published (which is irrelevant) he was a rebel and a leftist, a history buff, and among comic artists one of the best in illustrating the technical, from machines to military campaigns. And not to put too fine a point on it, but of all the creators involved, I don’t see evidence of anyone else having a longer relationship of admiration for Guevara. He probably had much longer to think his book through—it wasn’t just something that popped into his head after he watched The Motorcycle Dairies.

In my opinion, Spain’s Graphic Biography is the victor of this 3 week Battle of the Graphic Biographies. In all fairness, he had quite a head-start on the others. Aside from literally being the first published (which is irrelevant) he was a rebel and a leftist, a history buff, and among comic artists one of the best in illustrating the technical, from machines to military campaigns. And not to put too fine a point on it, but of all the creators involved, I don’t see evidence of anyone else having a longer relationship of admiration for Guevara. He probably had much longer to think his book through—it wasn’t just something that popped into his head after he watched The Motorcycle Dairies.

Star Rating: 4 ½ stars. Great work of political comic art.

Saturday, February 16

I haven’t read a book in Spanish in a long time… and I’ve never read a comic book, which has its own kinds of boundaries and flavours of language. Even when Spanish felt more or less as my proficient second language, jokes, double entendres and other palabra-play were never easy for me. I can count on one hand the number of punchlines I ever understood.

And so I kept stalling on this book, ¡Libertad! Because I can plainly see more and more, as I slowly crawl through these pages, that there is creativity here, and dedicated research–and passion for the story.

Title: ¡Libertad!

Author: Marise and Jean-François Charles

Artist: Olivier Wozniak, Benoît Bekaert

Published by: Ediciones Kraken, 2009 (Spanish version only – first published in French)

This book begins where most stories of Che end– his assassination at the hands of the CIA and Bolivian military and government officials.

“They say a man’s life flashes before his eyes before he goes,” the introduction reads, explaining that this is what this short comic is aspiring to do–what else could a comic book offer of a man whose impact on history was greater than many statesmen twice his age? It is for this reason that I like the format of this comic most, of all those that I have read. It is creative, yet reasonable.

Scenes jump from miltestone to milestone, as one would expect in an abridged biographical story. It begins in 1953, when Che is in Bolivia, slowly en route to Guatamala to work as a doctor, hopefully to participate in the modest reforms of President Jacobo Arbenz. He finds the woman who will become his first wife, but struggles to find meaningful work (the medical graduate complains about selling religious trinkets in the street before a car bomb explodes outside their apartment–to which his girlfriend, Hilda notes that they “may need a doctor now.”Guatemala is also where he meets members of the July 26th Movement, so it is his stage entrance into the Cuban Revolution. Scenes are taken from what we know, what is written of, the many meaningful points in Che’s life–points that tell us something of his character and capacity for leadership. This includes scenes like that of Che grilling the Cuban guerrillas who began firing on a peasant who had taken them by surprise (“What the fuck are you doing?” he says, “The land he tills isn’t even his–it’s for these people that we’re fighting!”). The book is showing, very efficiently, how “El Commandante” the man was built. Because Spanish is my second language, it’s impossible for me to tell the exact quality of the dialogue, here, but my literal translations remind me of a decent historical fiction film.

Scenes jump from miltestone to milestone, as one would expect in an abridged biographical story. It begins in 1953, when Che is in Bolivia, slowly en route to Guatamala to work as a doctor, hopefully to participate in the modest reforms of President Jacobo Arbenz. He finds the woman who will become his first wife, but struggles to find meaningful work (the medical graduate complains about selling religious trinkets in the street before a car bomb explodes outside their apartment–to which his girlfriend, Hilda notes that they “may need a doctor now.”Guatemala is also where he meets members of the July 26th Movement, so it is his stage entrance into the Cuban Revolution. Scenes are taken from what we know, what is written of, the many meaningful points in Che’s life–points that tell us something of his character and capacity for leadership. This includes scenes like that of Che grilling the Cuban guerrillas who began firing on a peasant who had taken them by surprise (“What the fuck are you doing?” he says, “The land he tills isn’t even his–it’s for these people that we’re fighting!”). The book is showing, very efficiently, how “El Commandante” the man was built. Because Spanish is my second language, it’s impossible for me to tell the exact quality of the dialogue, here, but my literal translations remind me of a decent historical fiction film.

Because the comic isn’t a documentary/biography style, with an outside narrator, I for one feel more submerged in the characters being presented: Che, Hilda, Fidel, and the minor characters that are there for pivotal moments: the Cuban who speaks with him on his way to Guatemala (in the book, he is presented as the first man to call Ernesto by the nickname “Che”), and on to the soldier who tends his wounds as he’s waiting to be killed.

Because the comic isn’t a documentary/biography style, with an outside narrator, I for one feel more submerged in the characters being presented: Che, Hilda, Fidel, and the minor characters that are there for pivotal moments: the Cuban who speaks with him on his way to Guatemala (in the book, he is presented as the first man to call Ernesto by the nickname “Che”), and on to the soldier who tends his wounds as he’s waiting to be killed.

The artwork is a very Tintin style, in my opinion, more common with European comics. I like the wash coloring–so much better than the digital colour randomness in the first book I reviewed. The illustrations aren’t stunning, but they’re certainly not bad, either. And there are a few compositions in the mix that give me the impression that the artist and author understood what was important to emphasize. For example, there is the rally in Havana Square at the dawn of the Cuban Revolution– you can literally count the frames of thousands of tiny Cuban people. If you see pictures, you’ll see that the magic of the moment in history was as much the masses as it was the words being spoken from the stage.

Despite the many positives of this book (especially when I compare it to other Che biographies), this work will reach few in North America. Because of its non-availability in English, and furthermore its large format, which makes it seem like a kids book) most of the comics readers I know would pronounce ¡Libertad! a lost cause before they even opened it. Where Sid Jacobson’s Che biography gets a 10 for accessibility, this book gets a 2. Very unfortunate, since the verdict on the books’ contents is, for me, the opposite.

Despite the many positives of this book (especially when I compare it to other Che biographies), this work will reach few in North America. Because of its non-availability in English, and furthermore its large format, which makes it seem like a kids book) most of the comics readers I know would pronounce ¡Libertad! a lost cause before they even opened it. Where Sid Jacobson’s Che biography gets a 10 for accessibility, this book gets a 2. Very unfortunate, since the verdict on the books’ contents is, for me, the opposite.

Rating: 4 stars. Some great biographical storytelling!

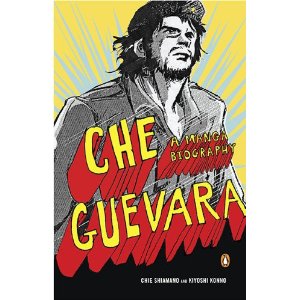

This week I’m reviewing CHE: A Manga Biography by Chie Shimano and Kiyoshi Konno, published in 2008 by Penguin Books

This week I’m reviewing CHE: A Manga Biography by Chie Shimano and Kiyoshi Konno, published in 2008 by Penguin Books

The last Che Bio I reviewed, I referred a few times to “historical inaccuracies”. In light of this Che comic, I’d like to re-characterize that distinction as “historical bias”. After all, history is open to interpretation, and there can be several “truths” welcome in a story where conflicting interests are concerned. Perhaps my beef with the book was that it was so totally American in its bias. For example, the section on the Bay of Pigs was through the eyes of a Cold-War-stricken Kennedy, not through the millions of Cubans having their country invaded (and taken advantage of by the USSR).

In my opinion, this Che biography shows an impression of Che through other eyes in the world. Like most Manga, this book comes from Japan, and approaches Che more as a folk hero than a strictly historical figure. Like most folklore, it is a light introduction to a subject–a simplified, more-or-less linear narrative.

…But before I jump into that, it has occurred to me that I never explained my rating system. When I’m reading a political comic, I’m looking for political and historical relevance, excellent research, storytelling capacity, and overall aesthetics (layout, the relationship between words and graphics). Each star, for me, represents one of these things in a five-star points system, and most works begin with one star just for bringing a political comic book into the world.

It always kills me when I see a book released by a major publisher (Penguin, in this case) where there is a typo on the first bloody page. Where the book is originally published is irrelevant; typos in an English translation are inexcusable on a 200 page book with a list price of $20.

I also find myself wondering how much of this book would make sense if I hadn’t already experienced other Che-related movies and books. There seems to be a lot of recycling here from Motorcycle Diaries. If it’s not original, at least the book is still passionate. Sid Jacobson’s CHE: A Graphic Biography (which I reviewed last week- listed below) seemed so sterile and uninspired, I wondered why or how the man got involved in writing the book.

Chie Shimano’s personal admiration for Che Guevera becomes clear about half-way through the book, as Che (now a Cuban diplomat) is traveling around the world seeking purchasers for Cuban sugar. In a last-minute itinerary change that threw his entourage into a panic, Che decided to visit the city of Hiroshima, site of the notorious U.S. bomb drop in WWII. Of everything in the book, I found this to be a high-point in the storytelling: it reveals something about both author and subject–and a connection, a passion for humanity against injustice, that they both share.

Despite this, and much stronger wording of the U.S. relationship towards Latin America (other Che biographies take note: we know you’re trying to be “unbiased”, but you can only use the words “meddling” and “intervention” so many times. Call a spade a spade: the word is “imperialism”), there remains some unfortunate truths about this book. Mangas are now prized around the world for their accessibility and entertainment value; maybe I’m expecting too much, but the dialogue here is so terrible. So scripted and campy. Again… I am reminded that this book is made with a nod to folklore–not just academic history.

There is a bibliography, but several passages that I believe required annotation, like a poem written to the passage of the Granma ship through the Caribbean, are not clearly noted.

CHE: A Manga Biography offers some original nuggets of innovation to what has become a collective storytelling of Che’s life. As well, it rightly contrasts with other more Amero-centric biographies, like Sid Jacobson’s take on the Bay of Pigs/Cuban Missile Crisis and U.S. intervention in Latin America. But ultimately, it still is not quite a “good” comic. Too many typos, campy scenes of heroism, and poorly-scripted dialogue.

Star Rating: 2 1/2 stars – a nice try.

(Part 1/4)

Some people are entirely against everything that he embodied. Some defend everything he ever did, whole-sale. Some swear to his beliefs, and yet decry the methods by which he carried them out. And still there are others who, 40 years after his death, wear his face on a t-shirt but don’t know his name.

Che Guevera. The middle-class Argentinian med student who went on to help launch the Cuban Revolution. He re-defined the rules of modern warfare, modernized the practical application of socialism, fought battles on three continents, and died at the hands of the CIA and their Bolivian counterparts.

No matter where you stake your claim in the spectrum, there is no doubt that Che was the socialist Dos Equis “World’s Most Interesting Man” for his time. But he was no pop star… the polarization of opinions of Che Guevera and his lasting image remain a testament to how much impact his ideas and his actions really had.

As someone who has read Che’s speeches, writings, seen the movies, been to various forums and seminars about the man’s life (including several in Cuba), I say this: the offerings of a 100-pg comic book covering the epic that was his life stand to face a tall order. Fidel Castro could probably write 100 pages about Che’s fingernails. It’s a challenge, regardless of the quality of writers or the artists; a challenge that I took an interest in a few months ago when I began to notice the high number of Che comic book biographies out there.

Most of them (and all the ones I’m reviewing here) were released at the same time –2008 to 2009. It may have been in response to the popularity of Diarios de Motorcicleta (The Motorcycle Diaries) released to critical acclaim in 2004. Nonetheless, not all are equal. Of the four I’ve chosen to review (there are six in total that I have come across, but the other two are out of print / not available in Canada) they come from three different countries and use vastly different angles and resources by which to tell their story. This is part 1/4 of my findings.

“CHE: A Graphic Biography” written by Sid Jacobson with artwork by Ernie Colon, was published in 2009 by Hill & Wang (under a section called “Novel Graphics”).

What immediately strikes me about this book is its accessibility. This copy was actually a Christmas present from my parents—if they found it, they obviously didn’t need to look too hard. The cover points out that both Jacobson and Colon are New York Times best-selling authors. This is graphic novel marketing and packaging at its most efficient.

To me, the inside reminds me about that old saying of books and their covers. It’s page 6 and I’m already confused. Chronology of the events really jumps around, as the author tries to write about two different bike trips that Ernesto went on at different times in his life. Coincidentally, I quickly take note that the artwork seems a little confused as well, if only in regards to the time period: Latino motorcycle thugs from the 1930s probably didn’t sport skull decals, black leather jackets and, well, modern-looking chopper motorbikes.

A plus is that the book takes the time to illustrate the political climate, more or less, of the major Latin American states at the time of Che’s trip, which I find useful and original—yet even this unique portion of the book tends to lack in terms of overall vision and context. For example, if the recurring themes in Che’s life revolve around wealth disparity (poverty, employment, suffrage) and U.S. meddling in the continent, then why are the descriptions of countries so scattered beyond this? Who cares that in 1951, Brazil ‘s executive branch consisted of a 9-man council? Proper context would have illustrated, perhaps, that over the last hundred years of Latin America there have been a thousand men who have come to power, elected or otherwise, on promises that were always broken…a continental legacy of despotism that is of down-right mythological proportions.

A plus is that the book takes the time to illustrate the political climate, more or less, of the major Latin American states at the time of Che’s trip, which I find useful and original—yet even this unique portion of the book tends to lack in terms of overall vision and context. For example, if the recurring themes in Che’s life revolve around wealth disparity (poverty, employment, suffrage) and U.S. meddling in the continent, then why are the descriptions of countries so scattered beyond this? Who cares that in 1951, Brazil ‘s executive branch consisted of a 9-man council? Proper context would have illustrated, perhaps, that over the last hundred years of Latin America there have been a thousand men who have come to power, elected or otherwise, on promises that were always broken…a continental legacy of despotism that is of down-right mythological proportions.

I find myself riding the fence with this book, looking for merit but noting mostly detractions, until the depiction of the last major battle of the Cuban Revolution, in Santa Clara, where guerrillas attacked a train car full of Batista’s soldiers. It is misleading at best, entirely historically inaccurate at worst.

The train was not attempting to escape; it was full of hundreds of reinforcements along with a ton of ammunition. Think about it; an army doesn’t “escape” in the middle of a battle—especially when their numbers are higher. Most of the 400-odd soldiers and officers survived, and were taken prisoner after a truce.

This scene and other historical inaccuracies, combined with scattered story-telling, poor research, and some eye-sore colour and design choices make this my least favourite of the biographies, despite its flashy cover.

My Rating: 1 star, and a pitying head-shake.

It was altogether a cry, at least at first, for unity amongst the colonies against their enemies, the French and native nations.

It was altogether a cry, at least at first, for unity amongst the colonies against their enemies, the French and native nations.